- 20 May, 2022

- 0 Comment(s)

- 4219 view(s)

- লিখেছেন : Saika Hossain

For the Muslims of Bengal, along with the Muslims of the whole Indian sub-continent the period till the twentieth century was a period of darkness, gloom and despair. The Muslims were suffering from decadence, ignorance, frustrations and were also held back by various customs and prejudices based on misinterpreted injunctions. As is usual in most backward societies, the worst sufferer from all these social ills of the Muslims, were their weaker counter parts i.e. the Muslim women. In the traditional Bengali Muslim Society, the women were the victims of the age old bondage and were segregated from the outside world. The so called Quranic injunctions and fatwas imposed on them by the orthodox Mullahs, Maulavis and Maulanas prevented most of the Muslim women from attending school outside home. There were several reasons why Bengali Muslim women lagged behind in society. The custom of strict purdah was an important hindrance for the female education. Abarodh deprived Bengali Muslims girls the access to education. Child marriage and conservative outlook were cited as the other causes for Muslim women’s educational backwardness. With the advent of modernization in the Muslim Society from the late nineteenth century, Muslim women began to be involved in greater spheres of activity. For the Muslim community in Bengal its transition from tradition to modernization was accompanied by the birth of an enlightened elite group. This section of the Muslim community tried to give a new leash of life to the society by their liberal and rational thoughts. It was within this process of transformation that Bengali Muslim women stepped out into a new arena. Many of these “New Women” went to schools for education and thereby they tended to break the traditional bondage. This first generation of educated Muslim women of the 1920’s tried to create their own identity and tried to uplift their status in the society.It was only in the twentieth century that Bengali Muslim women developed the logic of gainful employment for women, which was practically unknown in the nineteenth century. Moreover, while in the nineteenth century just a handful of women (all Brahmos or Christians) had ventured to do paid jobs, in the twentieth century a substantial number particularly the Muslim women of Bengal joined the workforce.The social prejudices which had hindered the education among Muslim women till the 19th century began to disappear gradually in the 20th century1. In the 1920’s and 1930’s a number of Bengali Muslim women got institutional education and began to acquire Graduate and Post Graduate degrees and few among them got into the teaching profession. Teaching as a profession for women won gradual acceptance because Bengali Muslim elite families who wanted education for their daughters were also anxious to shield them from contact with men outside the family circle. Realizing education as means to employment, few Muslim women were taking up the teaching profession, in Colonial Bengal, although an exact statistics cannot be obtained.

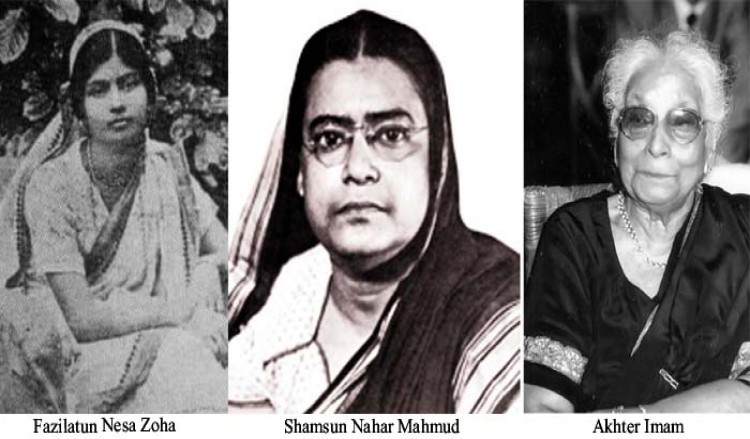

Among the few Bengali Muslim women who taught in colleges, Fazilatun Nesa Zoha (1905 – 1975) was one of the pioneers and was regarded a model for the women of the time. Born in 27th February 1905 in a lower middle-class Bengali Muslim family, in Tangail, with sheer determination, hard work and merit she had an excellent academic career. In 1921, in the matriculation examination she secured the first position from Eden Girls’ School and got a scholarship of Rs.15/- yearly. She stood first amongst the students of the Dhaka district in the Intermediate Examination also. Then she came to Calcutta to get admitted to Bethune College, to escape the criticism of the village society she knew. She was the first Bengali Muslim women to get into Bethune College and in 1923, she made history as the first Muslim woman to receive a Bachelor’s Degree from Bethune College in Calcutta.3After completing her bachelor degree, she went to Dhaka University which had been founded in 1921. She was not only the first among the Bengali Muslim women to study for an M.A, but was also the first Muslim female student at the University of Dhaka where she completed her M.A degree. Mohammad Nasiruddin wrote, “In those days, the attitude of Muslim society towards women was extremely old fashioned. They could not imagine a Muslim girl sitting with boys in a classroom. When Fazilatun Nesa went to attend classes in a sari, without wearing the burqa, occasionally stones would be thrown at her. But she remained undaunted. She earned a scholarship and through sheer hard work and grit fulfilled her ambition of receiving higher education.”4Her result in the M.A examination in 1927 created a stir in all circles and Nazrul Islam himself wrote a poem in her honour. While studying at Dhaka, she discarded the borkha. This was symbolic, signifying her defiance of the traditional norms. This was not an easy task, for she not only had to face criticism, but even threat of physical violence. She was fearless and nothing could daunt her spirit. In 1928, Fazilatun Nesa went to England for further studies on government scholarship and principally with the help of Saogat editor Mohammad Naseeruddin, braving sever social opposition. She married Shamsuj Zoha, a barrister she had met in England.

She chose education for a career. At the start of her career, she became the Assistant Inspector of Schools and later on, she became a Lecturer of Mathematics in Bethune College, her alma mater. She became the Head of the Department of Mathematics at Bethune College in Calcutta, and later it’s Vice- Principal during partition in 1947. It was a rare honour for Muslim women to become a Vice- Principal in a premier educational institution in those days.5 Post 1947, her family opted for Pakistan and Fazilatun Nesa and her family relocated to Dhaka and took charge of Eden College as its Principal. Fazilatun Nesa’s career graph was not as smooth as it seemed to be. She came from a lower middle class Bengali Muslim family in East Bengal. Sheer determination and of course exceptional merit led her from one academic success to another. She discarded the borkha while studying at Dhaka and Calcutta.6 This was also not an easy task, for she not only had to face criticism but even threats of physical violence. Fazilatun Nesa was fearless. Her voyage to England was also not a smooth one. The Minister for Higher Education in Bengal, Nawab Mosharaf Hossain was shocked that a Muslim girl should venture without purdah and think of going abroad. “Muhammadi” and “Hanafi”, the orthodox journals of that time vehemently criticised her for breaking the Muslim norms and traditions. Undeterred by criticism Faziltunnessa was equally unmoved by admiration. She spurned the love of Kazi Nazrul Islam, who was then at the height of his reputation as a poet and lyricist. She did not accept his marriage proposal and instead was more interested in building up her career and went abroad for further studies. Fazilatun Nesa strove to fulfil her aspirations with single minded determination. Fazilatun Nesa expressed her opinion against patriarchal society through her writings. In an article on female education which was published in Saogat in 1927, she advocated equal educational rights for women. In this article entitled “Muslim Nari Sikshar Prayojaniyata” she wrote in favour of the spread of formal secular female education along western lines where boys and girls would receive the same education.7 Such an education she believed would be beneficial for the Muslim society at large. She said that women have been confined in prison, which resisted the advance of knowledge in women’s mind. Citing the ideas of Roman Rolland and Bertrand Russell, Fazilatun Nesa said that freedom of women is a necessity and no society can prosper without recognition of women’s freedom.8 In an article entitled “Muslim Narir Mukti” published in Saogat in 1336 B.S. she boldly pleaded for women’s emancipation through education.9 Thus, we see that Fazilatun Nesa was the first Bengali Muslim woman to earn a postgraduate degree and the courage with which she took the first step in that direction was awe- inspiring.

Akhter Imam, also belonged to the first generation of Bengali Muslim working women. Akhter Imam (1917-2009) was an educationist; feminist activist who was born on 30th December 1917 in her maternal grandfather’s house at Narinda in the old part of Dhaka.10 She passed Matriculation in 1933 and Intermediate in 1935 from the Eden Girls’ High School and Intermediate College. Akhter Imam completed her Honours in Philosophy in 1937 from Bethune College in Calcutta, under the University of Calcutta. For having secured the first position among girls with honours, she was awarded Gangamani Devi Medal by the University of Calcutta. She did her Masters in Philosophy from the University of Dhaka in 1946.11 She was granted a government overseas scholarship from the Bengali Muslim Education Fund and so in 1952, she did her Masters again in Philosophy from University of London. In 1963-65 she pursued further research in Philosophy at the University of Nottingham, U.K.12 Akhter Imam started her career as an Assistant Teacher at Eden School. From the middle of the 1940s up to March 1956, she worked as Lecturer at Eden College with a scale of pay Rs.350-25-50013 (E.B. after 14th and 18th stages). After 1956 she joined Dhaka College on transfer as Professor. For several years since 1953, she had taught at the department of Philosophy of the University of Dhaka as a part-time teacher.14 In 1968-69, she became the first female Head of the Department and first female teacher of Philosophy in the University of Dhaka.

Shamsun Nahar Mahmud, a Bengali Muslim woman professor, was also a writer, educationist, teacher, social worker and later, a Parliamentarian in East Pakistan. She was born in an aristocratic, cultured and an enlightened family of Noakhali, which had taken to western liberal education and government employment very early and had crusaded for women’s rights. She was related on her father’s side to Fazlul Karim, one of the first Muslim graduates of Bengal. Her maternal grandfather, Maulana Abdul Aziz, was one of the founding members of the Muslim Suhrid Sammelani. Her childhood was spent in the strictest purdah in Chittagong. At the age of nine she was taken out of Dr. Khastagir’s Girls’ School in Chittagong in order to observe purdah.15 Shamsun Nahar again started her studies under a male Hindu tutor at home and she describes the thick curtain that separated her from her tutor which was a measure taken by her family to seclude her.16 Shamsun Nahar passed her Matriculation Examination with excellent marks which won her the permission to join college. Shamsun Nahar finally got admitted in Diocesan College, in Calcutta. The figure of the burqa clad Muslim housewife student was often a source of amusement for the relatively more emancipated Brahmo and Hindu women in that exclusive institution. This did not daunt her spirits and Shamsun Nahar surprised everybody by securing the twentieth place among all the students who had appeared for the Intermediate of Arts Examination under Calcutta University in 1928. She obtained her Bachelor’s degree with distinction in 1932 and was accorded a civic reception by Rokeya’s Anjuman-i-Khawmateen-i-Islam the same year.17Shamsun Nahar appeared for the Master’s examination as a private candidate and she successfully passed M.A. in 1942. Shamsun Nahar was married to the educated and magnanimous Dr. Wahiduddin Mahmud and her marriage opened the doors for her, to higher education and ended her days of confinement. Since then, there was no looking back, only a steady climb up the ladder.

Shamsun Nahar and her brother Habibullah Bahar jointly edited Bulbul from Calcutta in 1933. At the age of ten Shamsun Nahar started writing. Her first work Punnamayee (The Virtuous women) was published in 1925, when she was only seventeen years old.23 Her most well-known work was Rokeya Jibani, an authentic biography of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, her mentor and comrade in the crusade for women’s education. Rokeya Jibani (The life of Rokeya) was published from Calcutta in 1937. Her work entitled ‘Shishur Siksha’ was highly appreciated by Rabindranath Tagore who was experimenting with the ideal environment for the development of children at Santiniketan.24 In Prabasi, Shamsun Nahar wrote an article titled Shishu-Sahitya in which she explained the child psychology, citing the educational ideas of Frobel, Montessori, Harbert Spencer and Rabindranath Tagore.25 Her book Nazrulke Jemon Dekhechi (As I saw Nazrul) was about the common and firm belief that both of them shared, regarding the lamentable conditions of the women of the Bengali society. In 1926, Kazi Nazrul Islam visited their home from Calcutta with her elder brother Habibullah Bahar. On that occasion she did not get to meet him and she only heard him read and sing his poetry of protest from the inner chambers. Back in Calcutta, Nazrul wrote to Shamsun Nahar, ‘The girls in our country are very unfortunate. I have seen many girls born with enormous talent, but their potential dried up under demands of society.” 26 Shamsun Nahar acknowledges her deep debt to Kazi Nazrul Islam as a source of inspiration.27

Shamsun Nahar’s career started as a teacher in Sakhawat Memorial Girls’ School. Mrs. Shamsun Nahar Mahmud was appointed to the Government Service on 07/07/1939 as Professor of Bengali, Eden Girls’ College, Dacca. Her service was to be confirmed from 07.07.1941 and when she was on long leave Mrs. Khodeja Khatun of the B.E.S. was officiating from 1.10.1948 in her place.28 At the initiative of A.K. Fazlul Huq, the Chief Minister of Bengal at the time, Lady Brabourne College was set up in Calcutta in 1939 for the education of Muslim girls.29 Shamsun Nahar accepted the post of Lecturer in Bengali at the College in the same year and later on became the Head of the Bengali Department. In 1942, Shamsun Nahar appeared in the Master’s Examination as a private candidate and passed successfully. After the Partition of 1947 she joined the Eden College in Dacca. Shamsun Nahar was largely involved with issues concerning women throughout her life. In 1935, when the British passed the Government of India Act, women had no voting rights. Shamsun Nahar was one of the chief pioneers who on behalf of the Nikhil Bharat Mahila Andolan principally struggled for the voting rights of women. She joined many women’s organization and became active in the women’s movement in undivided India. She was a tireless worker for the All India Women’s Conference, National Council for Women in India, Bengal Women’s Education League, Bengal Provincial Council of Women and other women’s organizations. She got the opportunity to exchange views to discuss ideas with well-known women from India and abroad. In 1944, in recognition of her achievements in the fields of education and social welfare the British Government honoured her with the title of MBE.30 In 1961, in the drawing up of Muslim Family Law, her role was pioneering and on the question of women’s rights, she was extremely vocal. After partition of India Shamsun Nahar returned to Dhaka and had joined the Eden Girls’s College. She joined the government run women’s organization APWA (All Pakistan Women’s Association). On the question of women’s rights, she was extremely vocal.32 In 1961, in the drawing up of Muslim Family law, her role was pioneering. She was the president of the ‘Begum Club’ in Dhaka, from its inception till the end of her life. She died on 14 April 1964.

By the close of the 1920’s many Bengali Muslim bhadramahilas were coming out of the purdah on their own. The obstacles in their way had not vanished, although they were not the same as in the days of Rokeya. Fazilatunessa, Akhtar Imam and Shamsun Nahar were fewfirst-generation career women of the Bengali Muslim community who were not contended merely with fulfilment of their own aspirations. Throughout their lives they would work for the cause of woman’s education and for gender equality. They belonged to the first group of pioneer women humanists of the Bengali Muslim community. While Fazilatun Nesa would speak of a Nationalism based on cultural and linguistic affinity devoid of communal discord, Akhtar Imam relentlessly wrote on gender discrimination and on male chauvinism urging woman to assert their independent identity. They stressed on economic independence of woman. The message that empowerment was embodied in the earning woman was the maxim that Fazilatun Nesa and Akhtar Imam handed down to the young girls of the Bengali Muslim community. This was a decade which saw the rise of a professional middle class Muslim woman all over Bengal. Bengali Muslim woman in many instances physically discarded the burqa, the symbol of the andarmahal and stepped out into the world equipped with institutional education. These newly educated Bengali Muslim women embarked on teaching and other careers and their desire for education intensified. Teaching was considered to be one of the most acceptable professions for Muslim women and it employed the largest number of Muslim women in Bengal.From the 1920’s many educated Muslim women agreed with Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain about the damaging effects of purdah on women’s lives and capabilities and were leaving purdah. Most Muslim women who came out of purdah in the first half of the 20th century were not political or social rebels, but dutiful daughters who left purdah only with the sanction of their families, whether natal or conjugal.These professionally active Bengali Muslim women contributed in many ways to the greater visibility of Muslim women in educational, social and political action in the 1920’s, 30’s and 40’s Bengal. In these respects, the activities of Muslim women in colonial Bengal paralleled those of other Indian women at the same time. The phenomenon of independent earning power began to affect the lives of these working Muslim women by giving them a greater sense of individuality and an identity of their own in the society.

References

- Gail Minault, Other Voices, Other Rooms, in Nita Kumar (ed.) Women as Subjects, (Kolkata, Stree, 1994) P-119

- Shaheen Akhtar, and Moushumi Bhowmik (eds.) Zenana Mehfil, Bengali Musalman Lekhikader Nirbachita Rachana, 1904 – 1938, (Calcutta, Stree Publications, 1998,) PP 159-162

- Selina Hossain & Nurul Islam (eds) Dictionary of Biography, (Dacca , Bangla Academy, 1997) P-236

- Mohammad Nasiruddin, ‘Miss Fazilatun Nesa, M.A,’ Bangla Sahitye Saugat Yug (Dhaka, Noorjahan Begum, 1985) P-583.

- Shaheen Akhtar, Mousumi Bhowmik (eds), Zenana Mehfil, Op. Cit. Unchabhilashini Fazilatun Nesa, PP 159-171

- Akhtar Imam, Fazilatun Nesa and Muslim Women’s Higher Education and Liberation in Bangladesh, in Bibidha Rachana, (University Press, Dacca, 1994) PP 79-80

- Fazilatun Nesa Muslim Nari Siksar Prayojanijata, Saogat, Agrahayan, 1334 B.S. PP. 524-529.

- Uttara Chakraborty, Fazilatun Nesa O Akhtar Imam Atmaprakasher Itihas in Suparna Gooptu (ed) Itihase Nari Siksha, (Progressive Publishers, Calcutta, 2001) P-114.

- Fazilatun Nesa, Muslim Narir Mukti, Saogat, Agrahayan, 1334 B.S in Zenana Mehfil Op. Cit. PP-167-170.

- Selina Hossain Nurul Islam (eds.) Dictionary of Biography (Dacca, Bangla Academy, 1997), P-225.

- Uttara Chakraborty, Fazilatun Nesa O Akhtar Imam in Suparna Gooptu (ed) Itihase Nari Siksha, Op. Cit., PP-98-115

- Ibid P. 105

- Appointment Proceedings 44 (A), List No.35, 1939 – 1960, National Archives of Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Uttara Chakraborty, Op. Cit.

- Shamsunnahar Mahmud, Ami Jakhan Chhatri Chilam, Smriti Barshabani, Calcutta, 10th year 1357 B.S. also cited in Shahida Parveen: - Begum Shamsun Nahar Mahmud O Samakalin Nari Samajer Agragati, unpublished M. Phil thesis, (Rajshahi University, Rajshahi, 1986)

- Ibid.

- Anwara Bahar Chowdhury, Shamsunnahar Mahmud (Dacca, Bangla Akademy, 1987)

- Shamsun Nahar Mahmud Punyamoyee (Calcutta, Bulbul Publishing House, 1925).

- Anowara Bahar Chowdhury, Shamsunnahar Mahmud, Op. Cit., P-54.

- Shamsunnahar Mahmud, Shishu- Sahitya, Probasi, Shraban, 1350 B.S. P-268.

- Shamsunnahar Mahmud, Nazrulke Jemon Dekhechi (Calcutta, Navyug Prakashani, 1958), P-35.

- Shamsunnahar Mahmud, Nazrulke Jemon Dekhechi Op. Cit. P-22

- Report on Education A, 44(A) Bundle No.35 year 1939 – 1950 National Archives of Bangladesh, Dacca

- Sonia Nishat Amin, The Early Muslim Bhadramahila : The Growth of Learning and Creativity, 1876 to 1939, in Bharati Ray (ed) From the Seams of History, Essays an Indian Women, (Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1995), P.124

- Dr. Anowar Hossain, Muslim Women’s Struggle for Freedom in Colonial Bengal (1873 – 1940), (Calcutta, Progressive Publishers, 2003) PP – 165 – 166.

- Shamsunnahar Mahmud, Rokeya Jibani(Naya Udyog, Calcutta 1996).

- Selina Hossain & Nurul Islam (eds) Dictionary of Biography (Bangla Academy, Dacca 1997), P-250

- Ibid

- Rawson Ara Begum, Nawab Faizunnera O Purbanagar Muslim Samaj (Dacca, Bangla Academy, 1993) PP-77 – 80

- Begum Jahan Ara, Bangla Sahitye Lekhikader Abadan (Muktadhara, Bangladesh 1987), PP – 29-30.

- Gail Minault, Secluded Scholars, Women’s Education and Muslim Social Reform in Colonial India, (New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1998)

- Meredith Borthwick, The Changing Role of Women in Bengal, 1849-1905, (Princetons, Princeton University Press, 1984) P-311.

REPOST

Writer: College teacher

Pix: Collected

পোর্টালের দ্বিতীয় বর্ষপূর্তি উপলক্ষে পাঁচটি বেশি পঠিত লেখা পুনঃপ্রকাশের আজ পঞ্চম লেখা।

0 Comments

Post Comment