- 18 October, 2020

- 0 Comment(s)

- 1810 view(s)

- লিখেছেন : Maitree Devi

Property and inheritance law in India (theoretically the statutory laws are being followed for Hindu women) and Bangladesh are practiced on the basis of statutorily approved religious personal laws of the community within kinship-based patriarchal societies, in contradiction to the promise of equality by the modern constitutions. In common parlance, the term ‘property’ means immovable or movable (land, money, house, gold, jewellery or other valuables) objects. Women’s entitlement as well includes resources — nutrition, clothing, shelter, individual space, medical care, education and emotional care, and so on — within the family, which determine the notion of legitimacy in the household for women that go beyond the system of state-enforced laws on property relations.

Legal Framework for Minority Women: India and Bangladesh

In India and Bangladesh, the laws pertaining to family, marriage, divorce, succession, maintenance, property etc., are practiced on the basis of statutorily approved religious personal laws of the community within kinship-based patriarchal societies.

In the context of women, they are cast primarily as caretakers, mothers and wives in need of protection. The problems of blatant discrimination or hidden biases in the customs, policies, law do make women deprived of entitlements and capabilities. For an example, law reformed proposal by Indian legislation on domestic violence that was more concerned with the protection of the institution of the family and marriage, and women’s roles within this institution.

The laws in the both countries continue to reinforce assumption that a woman surrenders her right as soon as she enters in a marital relationship and her entitlements are subject to the private sphere/family matters, community and personal law/norms (Kapur, 2005). Consequently, in regards to the debate of Uniform Civil Code (in India) and Uniform Family Code (in Bangladesh) it can be argued that it is compromised stand of the state when it shows its desirability to replace the personal laws with a uniform one and wants to proceed only when the communities themselves are ready to accept them.

In India

In post-independence India, in regards to the issue/question of property rights for women, subsequently, some positive steps have been taken to ensure property rights for Hindu women (despite some lack in ensuring actual ‘equality’), which are- the Hindu Succession Act, 1956; the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956; the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005 have all sought to grant women their rightful property from their husbands or fathers to give equal rights to daughters in Hindu Mitakshara coparcenary property. The most significant change in the 2005 Amendment is the omission of section 4(2) of the Hindu Succession Act of 1956, as it brings agricultural land at par with all other forms of property); Furthermore, Hindu Marriage Law (Amendment) Bill in 2010; The Rajya Sabha proposal in August 2013 (approved a proposal to make divorce easier for women as it has a provision for wives to obtain a share in their husbands’ immovable property after “irretrievable breakdown” of marriage).

However, for Muslim women, the legislature and eventually even the judiciary have not yet changed the Muslim Personal Law in favour of Muslim women’s interests. The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, passed in 1986, diluted the Supreme Court’s revolutionary verdict in the ‘Shah Bano case’ (Mohd. Ahmed Khan Vs. Shah Bano Begum, 1985, 2 SCC 556) and, ‘theoretically’ it denied utterly destitute Muslim divorcees the right to alimony from their former husbands. The Shah Bano case challenged Muslim Personal (Sharia) Law and triggered a debate, paved the way for Muslim women’s fight for justice. Nevertheless, in the milieu of the representation of Muslim women as worst victim by the Sharia laws, Flavia Agnes opined that Muslim women in India are not devoid of rights; challenging their personal laws in the Supreme Court is not the only recourse open to them.

In Bangladesh

Independent Bangladesh after 1971, carried forward all Pakistani laws, rules, and regulations along with ‘The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act’, 1937 and Hindu Women’s Property Rights, 1937. The legislature in contemporary Bangladesh, amended some significant sections of the Muslim Sharia Act 1937 and Muslim Family Laws Ordinance, 1961, in order to accommodate certain liberal values. This includes the criminalization of verbal talaq and remarriage without the written consent of the spouse, the legal entitlement of economically vulnerable women with children to maintenance after divorce for more than three months, custody of children for women, and so on. According to the amendment in Section 7(6) Ordinance, 1961 the divorced parties can remarry without performing any intermediary arrangement i.e. ‘Hilla’. This amended Sharia law is known as the ‘Muslim Personal Law’ (Kamal, 2014). Further, a lot of different progressive legislations and amendments on previous laws for women’s advancement have been formulated under different political regimes.

The Muslim Marriages and Divorces (Registration) Act, 1974 made registration compulsory, Section 3 of the Act provides ‘every marriage solemnized under Muslim law shall be registered in accordance with the provisions of this Act’ and provides for the licensing of Nikah Registrars.

Some other legal initiatives such as the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1980 and its amendment in 1986; Cruelty to Women Law 1983; the Family Court Ordinance, 1985 with exclusive jurisdiction on matters relating to marriage, dowry, maintenance and guardianship, and custody of children for every women regardless any religion, class and caste; Prevention of Repression against Women and Children Act, 2000; Acid Crime Control Act, 2002; Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act, 2010 contributed to the contentious debates regarding their prospective significance towards women's rights in Bangladesh.

By contrast, for Hindu women, the judiciary has been limited by the lack of provisions for inheritance and property entitlements in Hindu personal law 1937. The Hindu personal law (Dayabhaga School) followed in Bangladesh did have a few provisions for Hindu women to inherit property (absolute ownership of streedhan, and limited ownership of widow’s estate) and the female heirs were not succeeding absolutely. Further, a Hindu woman is entitled to her lifetime maintenance by her husband, provided she is not proved unchaste. The maximum entitlement a Hindu woman did have was the right to be maintained by male relatives of her natal family before marriage and of her husband’s family after marriage. In the case of Hindu women, the Marriage Act Registration of 1872 was not acknowledged in the legislations and there were no provisions for ‘separation’ and ‘divorce’ for Hindu women (Sharma, 2004).

It has been observed that in the case of Muslim community in Bangladesh and Hindu’s in India, despite the presence of progressive laws and legal platforms, neither Muslim nor Hindu women have benefitted from the same because of feeble enforcement and enactment of these laws in actuality. Further, we see that both Hindu (In Bangladesh) and Muslim (in India) women’s inheritance rights have been subordinated to the ‘greater cause’ of community rights, and the communities in question have presented their group rights as conflicting with and in opposition to women’s rights. Such considerations on the part of community leaders and the state are informed by dominant socio-cultural presumptions, derived from religious traditions, which continue to see women as dependent on men. The state’s attitude towards the minority communities (Muslim [in India], Hindu [in Bangladesh], Buddhist, Christian communities and indigenous tribes in both countries) through policies (and politics) like land distribution, ‘Vested Property Act’ (in Bangladesh), forced demographic changes etc., have only aggravated the denial of minority women’s entitlements.

In the name of secularism and ‘special privileges’ to minorities, the subordination of minority women in India and Bangladesh have compounded by the government’s reluctance to enforce any change in their customary practices and traditions. The equality of citizenship stands compromised here by the selective intervention of the state and by the very system of religion-based personal laws inherited from colonial and pre-colonial times as the laws of state. However, the absence of legal platform is only one aspect of gender discrimination. The other obstacles towards property rights for women are structured in the socio-economic reality of the patriarchal cultural kinship-based ‘private’ and ‘public’ spheres and unattached legislative rights.

Author: Maitree Devi, PhD Scholar

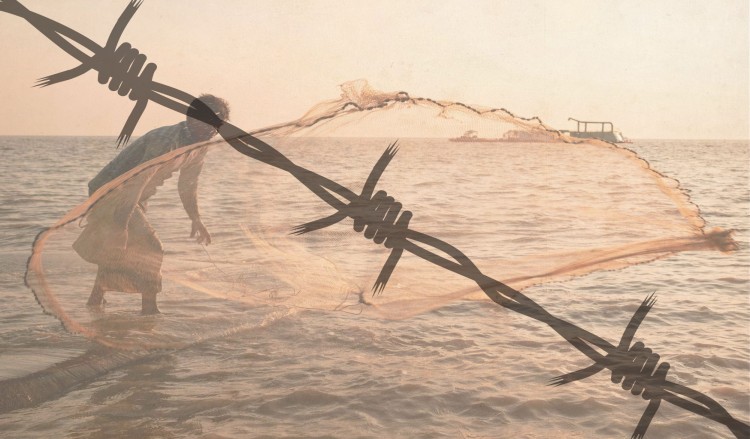

Picture courtesy: Internet

0 Comments

Post Comment