- 08 October, 2023

- 0 Comment(s)

- 1779 view(s)

- লিখেছেন : Amartya Banerjee

There lies a woman, along with five other elderly people in an unmarked grave. Little one may guess how this frail, unknown woman once shaped the equality movement in her primes. This was way before the suffragettes got their first taste of freedom, or Simone de Beauvoir wrote her seminal thesis on ‘The Second Sex’. Yet Sarah Dearman (née Chapman), as early as in 1888 when she was barely twenty years old, planned and steered one of the first ever women-led industrial actions against the famous Bryant & May Matchmakers’ Factory in Bow, London. The movement garnered support from people like Annie Besant and Herbert Burrows, the renowned social activists during their times.

Match making was considered as one of the most important commercial activities in nineteenth century England. At that time a large chunk of the poor population earned their daily breads through their employment in various match making factories strewn across the land. According to a report published in 1897, there were 25 match making factories in Britain, employing approximately 4,200 people, of whom 2,700 were adults. Nearly 1500 of the employees were aged between 14 to 18 years. Needless to say, a large number of the workforce constituted of women and children, mostly in their teens and they had to toil under horrible working conditions. Apart from the lack of regular hygiene in the factories, the workers were also exposed to white phosphorus, a highly poisonous substance which was then a key ingredient in match making. It is to be noted that by 1850, the element of red phosphorus was discovered, which was far less toxic compared to its white counterpart and could be efficiently used in the match making process. But the owners of the match making companies refused to use red phosphorus as their ingredient in order to maximize their financial benefits, as the red substance cost more than the white. As a result, even as late as in 1897, out of the 25 match making factories in Britain, 23 factories used the toxic white powder, which caused a serious illness called the ‘phosphorus necrosis of the jaws’. The disease had a 20% mortality rate amongst its patients.

The Bryant & May Match Making Company was founded in 1843, and during the 1880s it employed nearly 5000 people. Most of the workers were females and of Irish descents. The workdays were at least 10 hours long. But it could also go up to 13 or even 14 hours per day without any suitable reason, quite regularly, without any kind of obligation in the organization. Depending on the type of work and age, the workers were officially paid 1 shilling per 40,000 matches or less. Those of the workers, who were below the age of 14 years, were paid weekly wages amounting to 4 shillings per week. None of the employees were protected by the Factory Acts. Thus no kind of social security or health benefits covered them during their employment. The factory was poorly ventilated, and most of the time the supervisors and other bullying staffs with higher authorities fined the women and children who were employed, citing trivial reasons, and thus they robbed the latter’s hard-earned shillings leaving them in abject pecuniary conditions.

Previously there had been incidents of strikes and protests against the match making companies in 1881, 1885 and 1886 – but they were mostly for higher wage, better working conditions and abolition of illegal punitive measures. In 1888, during the strike at the Bryant & May Matchmaking works, the workers officially raised their voice for the first time, against the ill effects of white phosphorus and demanded its abolition as an ingredient in the factory. During the month of June, 1888, the workers under the leadership of Sarah Chapman approached Annie Besant and Herbert Burrows, highlighting their poor working conditions and other concerning matters of the factory. Dr. Besant published an article describing the abject condition of the workers. The authorities in response fired one of the employees on trivial grounds, suspecting that she had acted as the traitor and leaked information regarding the factory conditions outside, to the Besants for publication. This incident took place on 2nd July, 1888. The article written by Dr. Besant was published on 23rd June.

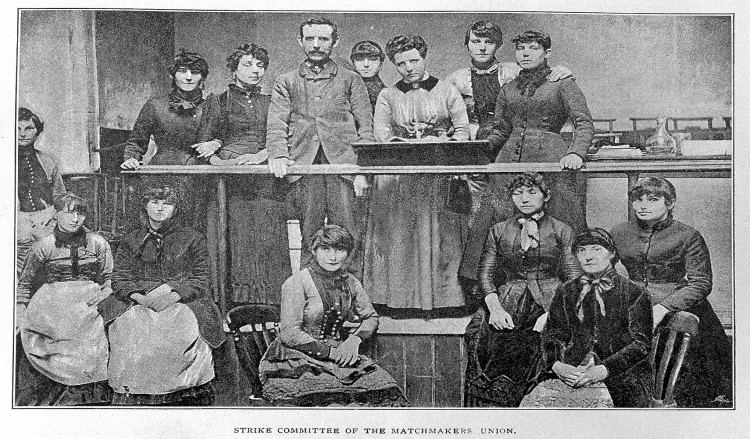

From 3rd July, 1888, the Matchmakers’ Strike began. No less than 1400 women and girls refused to work and they walked out of the factory in unison. By 6th July the factory had to stop all its activities, and about a hundred women led by Sarah Chapman marched down the banks of the Thames to meet Annie Besant, who was trying to further propagate the news of this movement to the outer world. A deputation of women led by Sarah, (some say the other members accompanying her were, Mary Cummings and one Mrs Naulls) met Charles Bradlaugh, and two other members of the British Parliament. Public meetings were arranged outside the factory which was addressed by people like Annie Besant and Sarah herself over the days as the events unfolded. Charles Bradlaugh spoke in the British Parliament regarding the matchmakers’ strike, making a clear case for the workers in front of the ruling echelons of the country. The authorities at the factory had to back down at last and agree to most of the demands of the workers in the strike.

But another twenty years will pass till the British Parliament will officially abolish the use of white phosphorus in the match making factories, in 1908, also making the ruling effective only from 1910 in a prospective declaration. Apart from Sarah Chapman, Mary Cummings or Mrs Naulls, one now finds the names of Alice Francis, Kate Slater, Mary Driscoll, Jane Wakeling, Eliza Martin and others who participated and led this movement, and later formed ‘The Union of Women Match Makers’ whose inaugural meeting was held at the Meeting Hall of Stepney, London on 27th July, 1888. Chapman also represented the union at the two Trade Union Congresses held in London (1888) and Liverpool (1890) respectively. Later in December, 1891, Sarah Chapman married Charles Henry Dearman and moved to Bethnal Green, having five children thereafter. Mr. Dearman died in 1922, but Sarah lived her life until November, 1945, when she passed away in London, aged 83.

Sarah Chapman, although led a long life, and after the strike she had a well-waged position in Bryant & May, she had to be buried in an unmarked grave along with five other people and silently took exit from the stage. In 1918, the women of England and Ireland got voting rights. Four years after Sarah’s death, in 1949 Simone de Beauvoir published her work, ‘The Second Sex’ which was to gain worldwide acclaim after its appearance. Although Mary Wollstonecraft published her work entitled ‘A Vindication of Rights for Women’ as early as in 1792, the modern waves of feminism mostly appeared during the twentieth century and mostly after the second quarter of it. Individual figures like Sarah Chapman, kept alive the flame of the ‘mouvement féministe’ and tried to be the spark which will ignite the idea of a generation of ‘nouvelles femmes’ or ‘new women’ in the light of freedom and equality, but later only succumbed to the yellowing pages of forgetfulness. In 2020 there was an attempt to remove the mound of Sarah’s grave for a beautification drive at Manor Park but a few organizations resisted the government’s efforts and could protect her grave from an imminent danger of destruction. A Blue Plaque has been recently erected in the memory of the Matchmakers’ Strike which further vindicates the historical significance of Sarah’s work.

We remember her today from the forgotten and yellowing pages of the past, only to remind ourselves about the countless unsung heroes who have gone on through this path, and whose immense contribution and devotion paved our ways and bore fruit for us, which we so deliciously enjoy today, sometimes even forgetting our duties to execute.

0 Comments

Post Comment